Introduction: The Magic of Depth in Photography

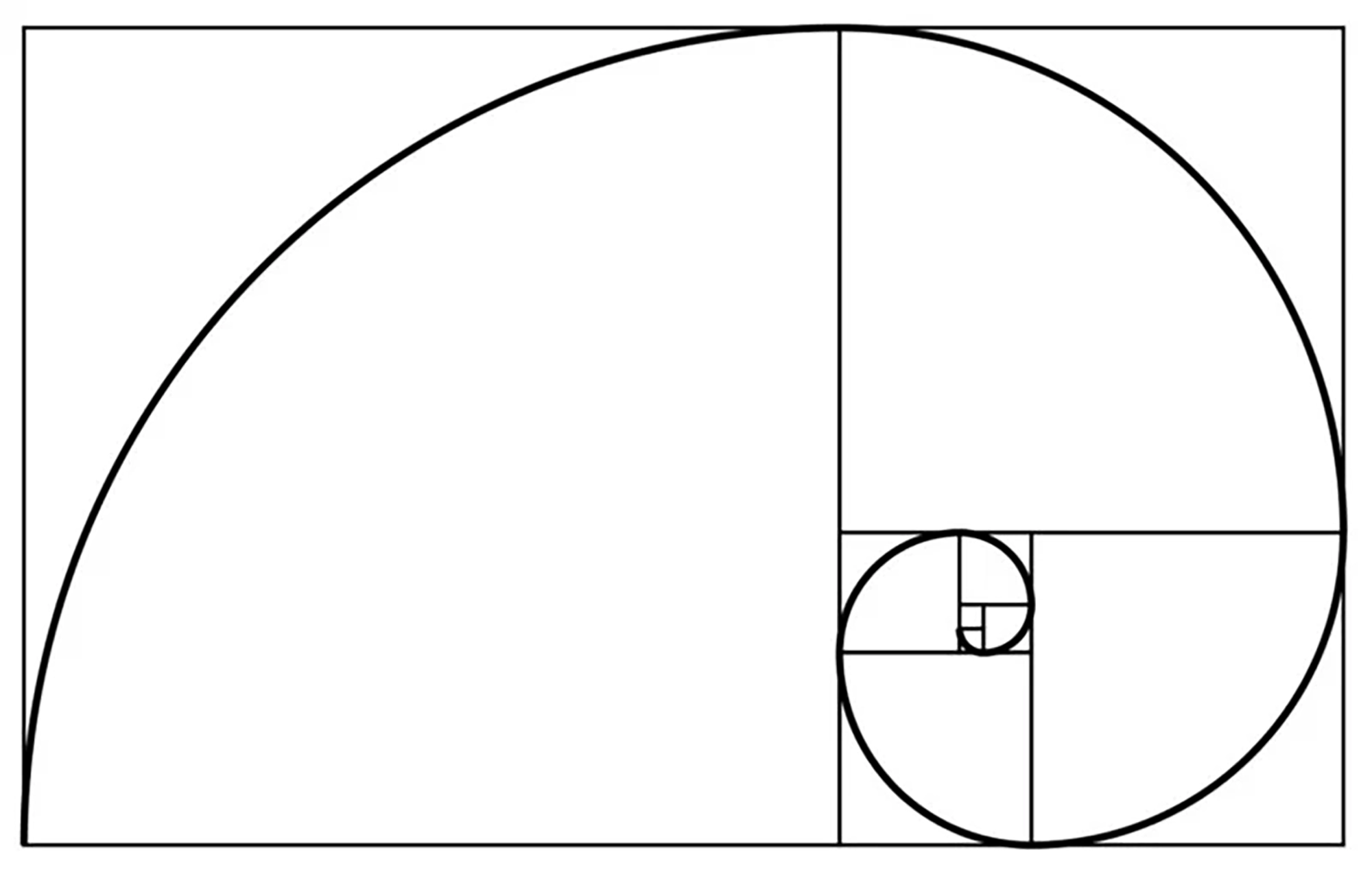

Foreground interest is a powerful compositional tool in photography that adds depth, leading to more dynamic and engaging images. By incorporating elements in the foreground, photographers can create a sense of three-dimensionality, drawing viewers into the scene. This technique is vital in transforming flat images into vivid, life-like experiences.

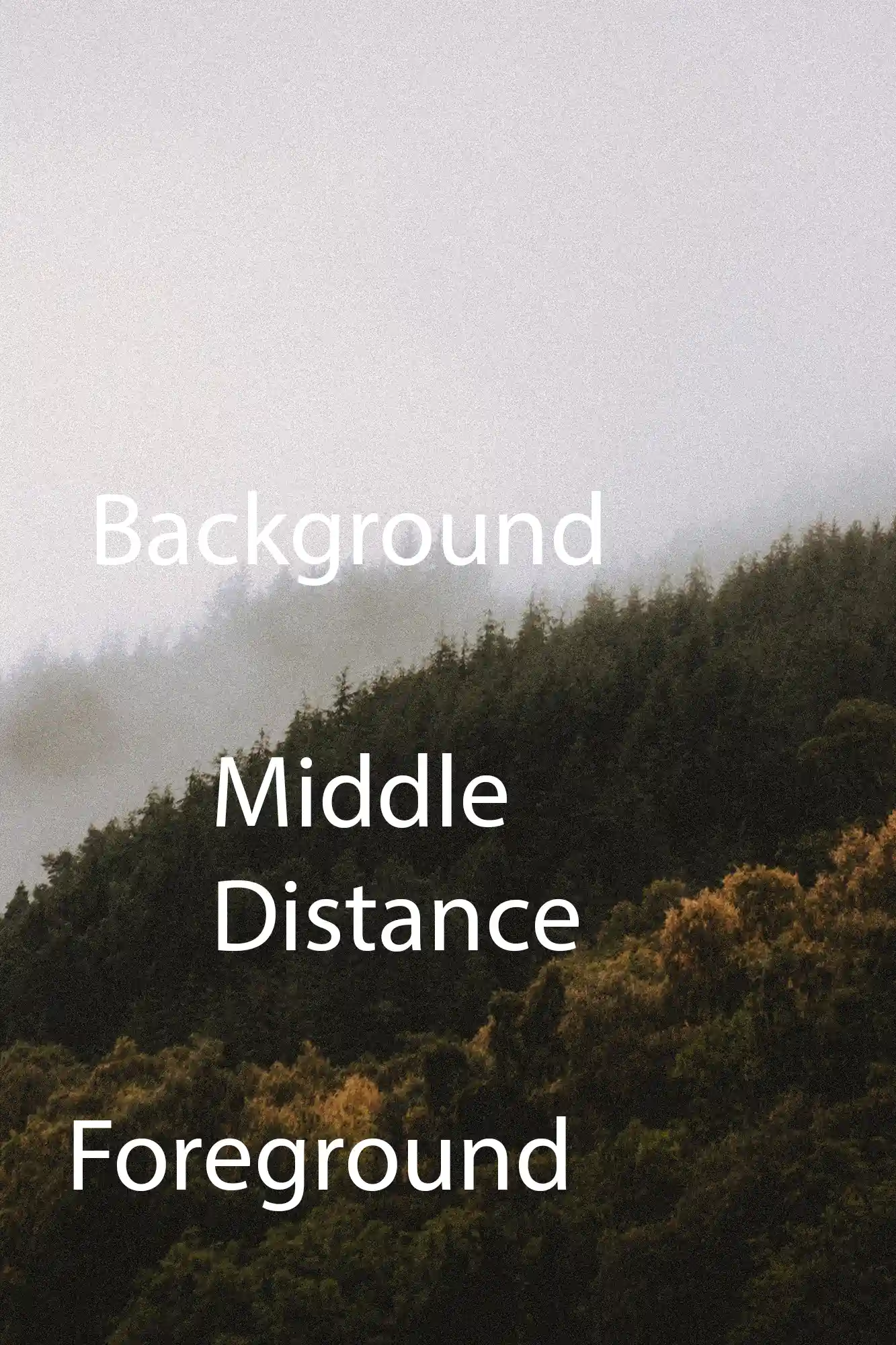

Understanding Foreground Interest and Depth

Foreground interest involves strategically placing objects or elements in the lower part of your frame, which are closer to the camera compared to the main subject. This layering technique not only adds depth but also helps in guiding the viewer’s eye through the image, creating a narrative and a sense of space.

O Carroll, B. (2016). 28 Composition Techniques That Will Improve Your Photos.

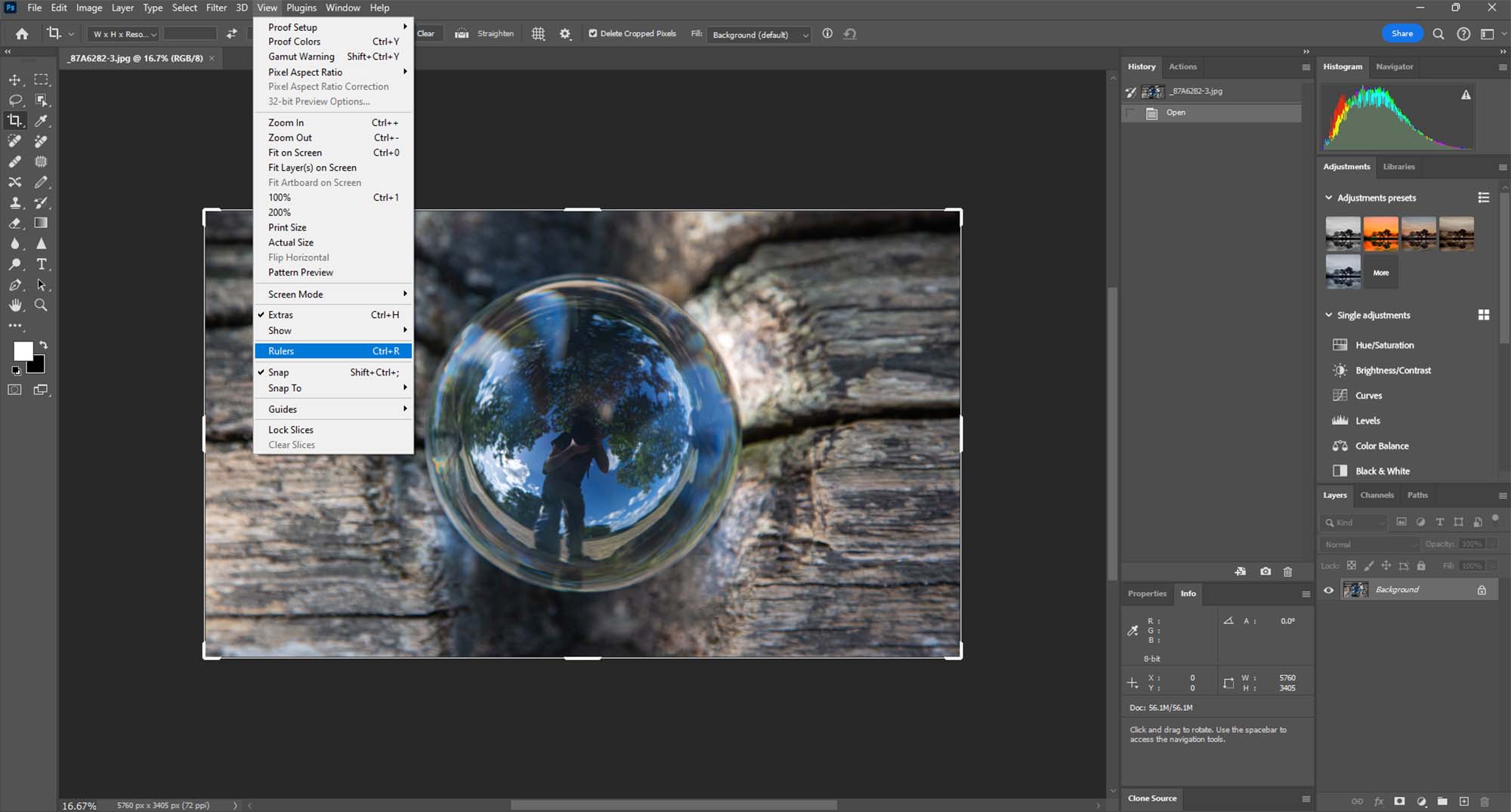

Creative Process: Implementing Foreground Interest

- Identifying Elements: Look for elements that can serve as interesting foreground subjects – rocks, flowers, urban artifacts, or even shadows and light patterns.

- Composition and Placement: Place these elements in a way that they lead the eye towards the main subject. The placement should feel natural and not forced.

- Balancing the Scene: Ensure that your foreground interest complements the scene and doesn’t overpower the main subject.

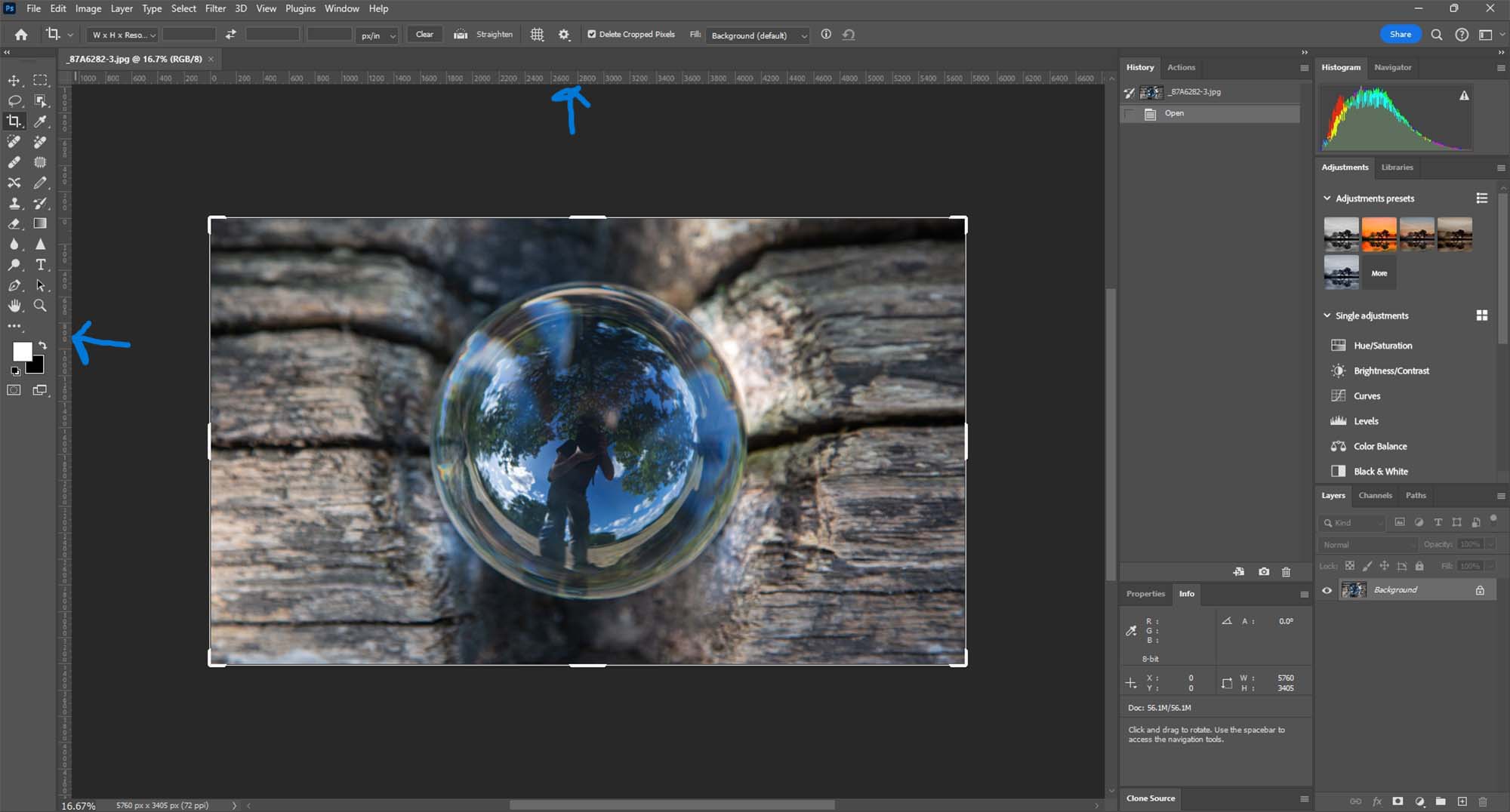

Tips for Photographers

- Wide-Angle Lenses: Use wide-angle lenses to exaggerate the sense of depth. They are excellent for capturing both the foreground interest and the background.

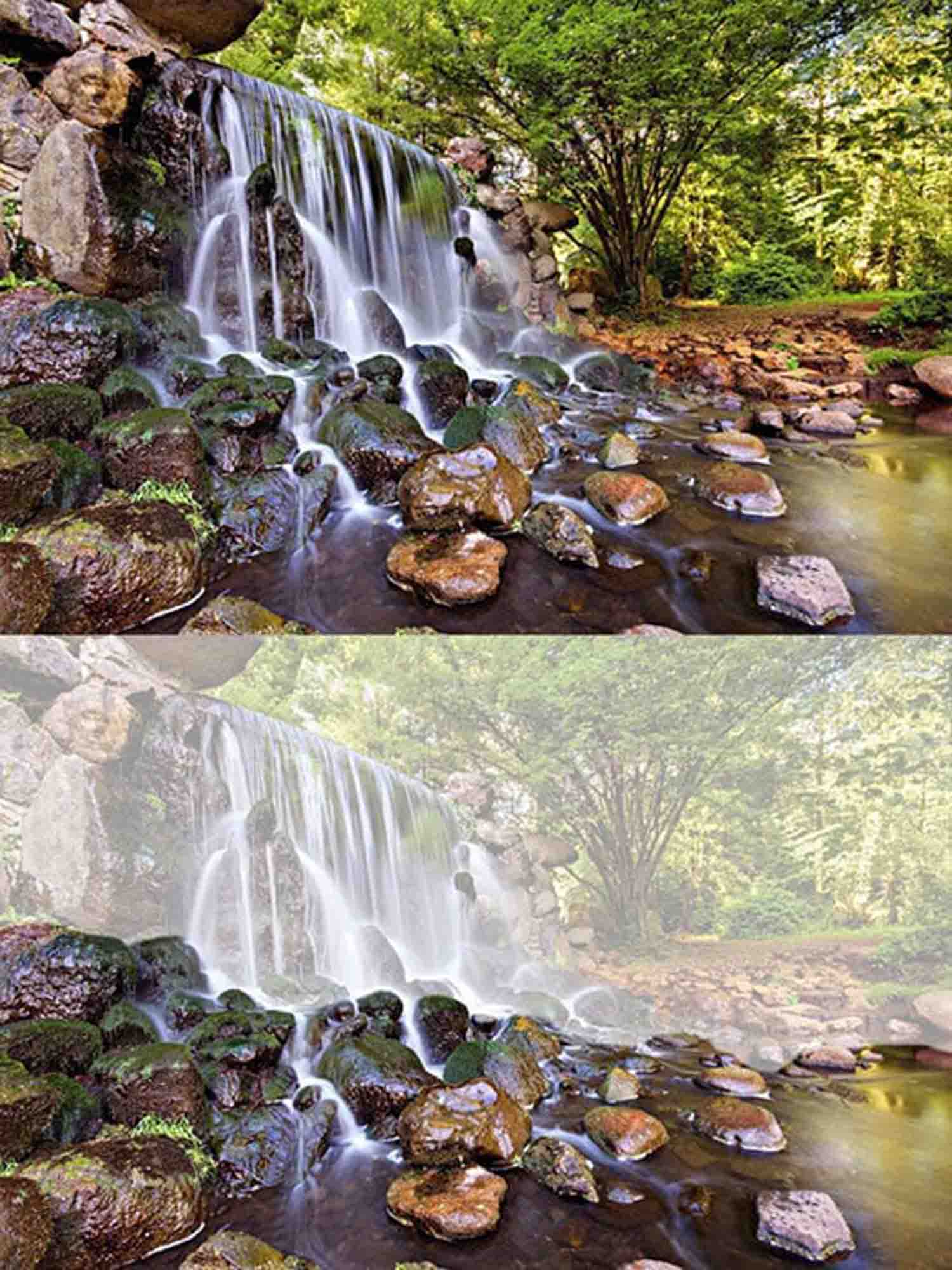

- Aperture Settings: Experiment with aperture settings. A smaller aperture (higher f-number) keeps both the foreground and background in focus.

- Trial and Error: Not every element makes good foreground interest. Experiment with different objects and see how they affect the scene.

- Focus Stacking: In landscapes, try focus stacking to keep the foreground and the distant background sharp.

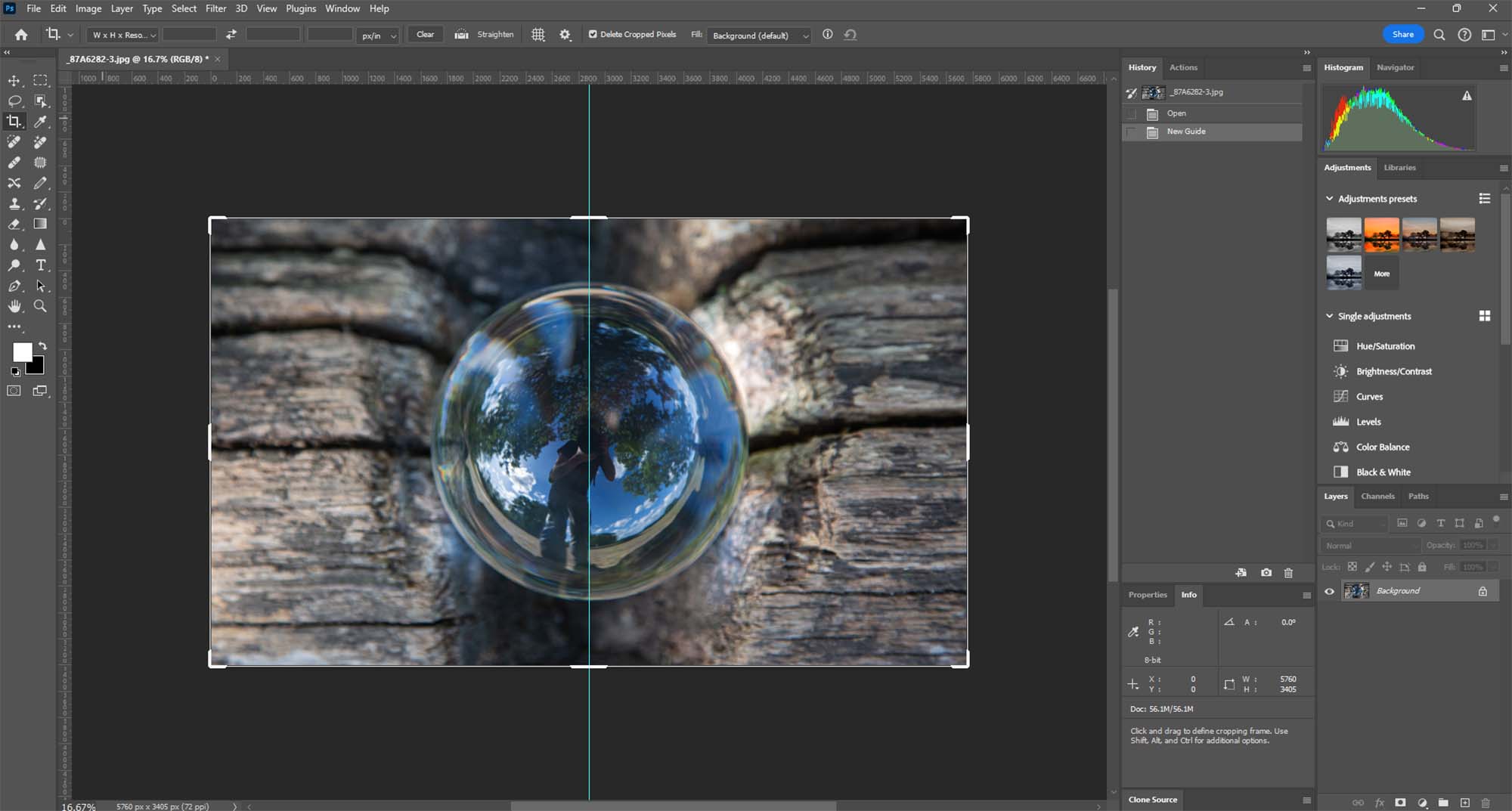

Advanced Techniques in Using Foreground Interest

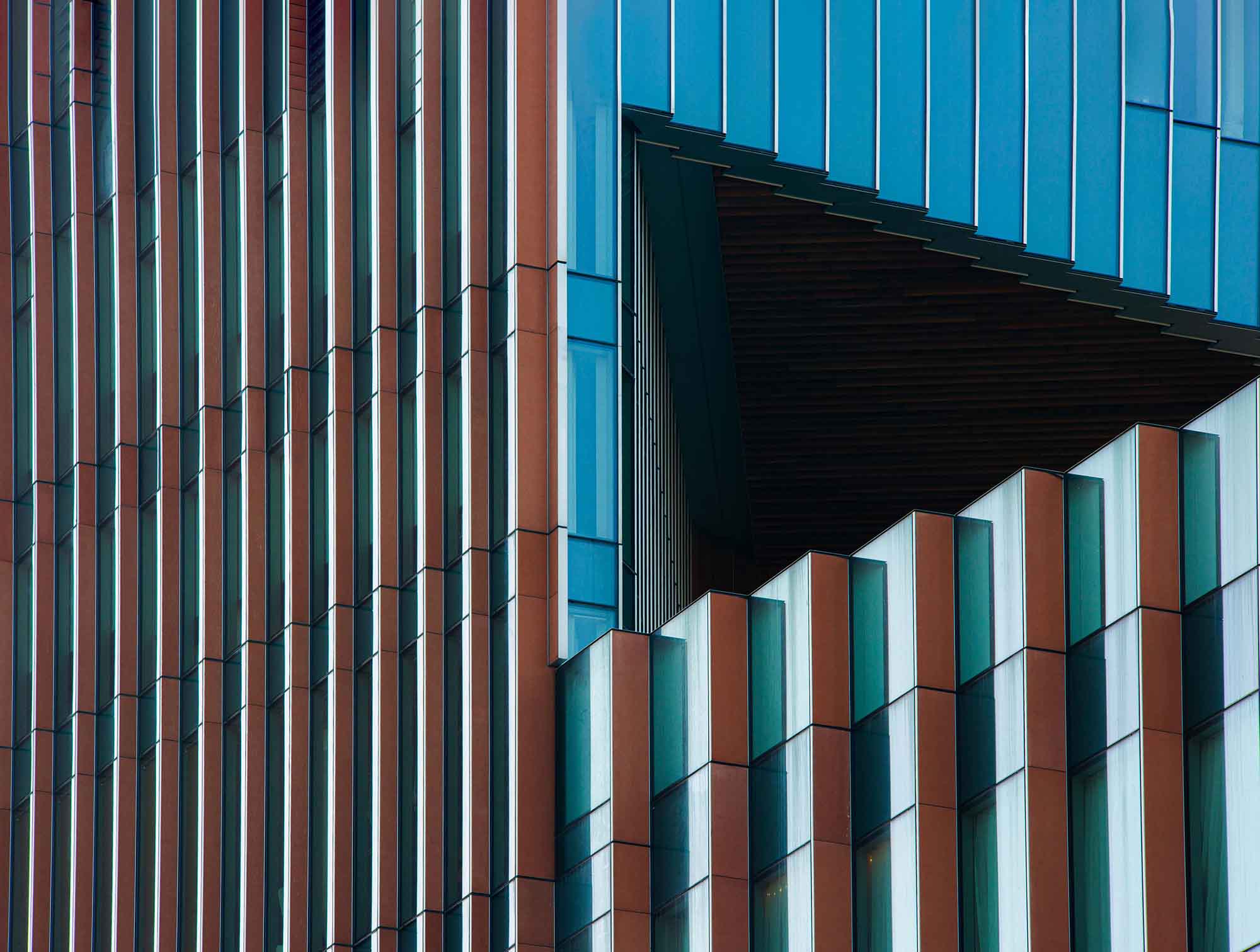

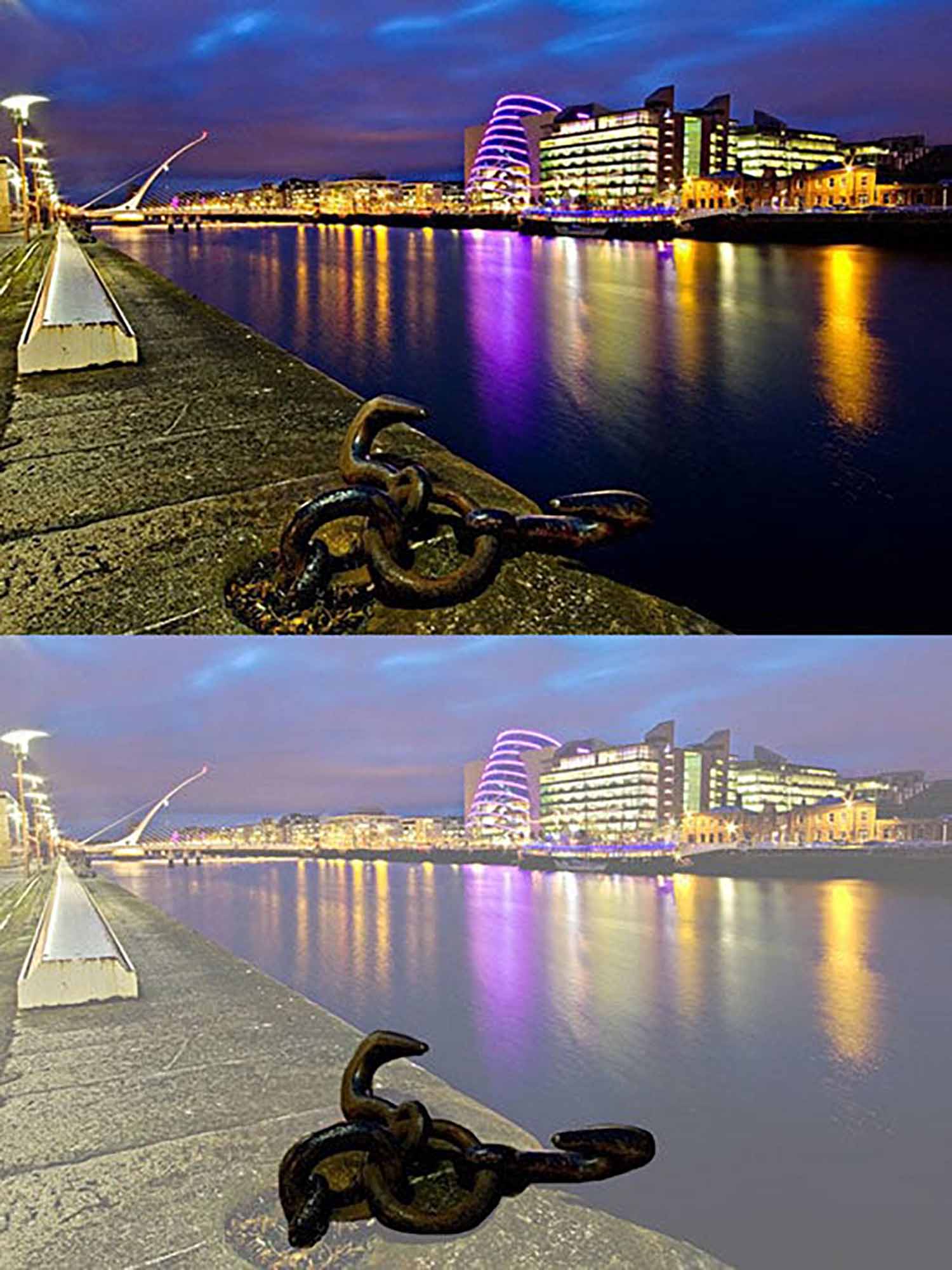

- Leading Lines: Use natural or urban leading lines in the foreground to guide the viewer’s eye towards the main subject.

- Framing the Subject: Elements in the foreground can act as a frame, subtly enclosing the main subject for added depth and focus.

- Reflections as Foreground: In water bodies, reflections can serve as an interesting foreground, adding symmetry and depth.

Practical Applications in Various Genres

- Landscape Photography: Use rocks, flowers, or foliage in the foreground to add depth to scenic views.

- Urban and Street Photography: Urban elements like pavement patterns, street furniture, or even a passerby can serve as engaging foregrounds.

- Macro Photography: In macro photography, a shallow depth of field can make the foreground elements blur into beautiful bokeh, adding depth.

Conclusion: Elevating Your Photographic Perspective

Incorporating foreground interest is a skill that elevates your photographic perspective, transforming ordinary scenes into captivating stories with depth and dimension. It requires practice, a keen eye for detail, and an understanding of how different elements in a scene interact with each other.

O Carroll, B. (2016). 28 Composition Techniques That Will Improve Your Photos.

References

O Carroll, B. (2016). 28 Composition Techniques That Will Improve Your Photos. [online] PetaPixel. Available at:

https://petapixel.com/photography-composition-techniques/

[Accessed 12 Dec. 2023]